It is not a new story but one that continues to grow in importance and with a deeper and more alarming degree of concern. With an aging baby boom population along with sudden and unexpected health issues like a pandemic, the country’s nursing shortage is morphing into a critical need stage requiring additional if not immediate attention.

In Pueblo, places where two of Colorado’s premier nursing schools are located, newly minted candidates are funneling into the pipeline each year. And just in time.

In Colorado and nationwide, says the website nursejournal.org, there is an acute and ever-growing shortage of qualified professionals to fill this void. It is estimated that by the end of this decade there will be a shortage of 175,000 registered nurses across the country, despite an 11 percent annual growth rate in the profession.

Pueblo Community College and Colorado State University-Pueblo have for years been graduating and placing nurses into jobs across a region larger than even many U.S. states. Nurse openings do not remain open very long.

“A lot of our students will have jobs before they graduate,” said PCC’s Director of Nursing, Eva Tapia. That doesn’t mean placing an unqualified nurse but rather placing someone trained in the duties and responsibilities of a nurse yet under the mentorship of a nurse assigned to monitor his or her performance.

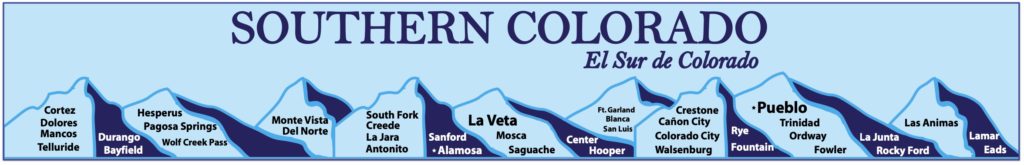

Besides Pueblo, PCC also operates nursing programs at its satellite campuses in Cortez, Durango, Fremont County and Mancos. The benefit of having these programs is providing smaller communities with someone who knows the people and who will remain in the community for the long term.

Graduates of the two-year PCC program leave with state licensure and are bestowed the title of Registered Nurse along with the privilege of working as such across the state of Colorado.

Each of PCC’s nursing students is, like all students, required to take the core general education classes, said Tapia. Nursing students, she said, are then required to have “750 clinical hours in the (nursing) program spent in hospitals and clinical settings.”

Ten minutes from the PCC campus on the city’s far northeast side, Dr. Joe Franta runs CSU-Pueblo’s College of Health, Education and Nursing. CSU-Pueblo’s nursing program is now nearing its sixth decade of graduating nurses.

“Our first class,” said Franta, “had about twenty students.” Today, Franta estimates, “our peak semester (spring) we have 300 students” in the program.

Still, while the rate of qualified graduating nursing candidates may seem able to fill job openings, jobs are occurring at an even faster pace. While the aging baby boom is creating more demand for nursing candidates, there is also the issue of aging baby boom nurses who are now retiring and leaving the profession.

Also creating holes in the nursing fabric is the stress level endemic in the profession, a level exacerbated by the COVID pandemic where more than a million Americans died of the virus and several million more were hospitalized but survived. Franta says the long hours necessitated by the patient overload and the constant exposure to pain, suffering and death naturally took a toll.

Managing stress that is inherent in nursing is addressed very seriously in both the PCC and CSU-Pueblo nursing programs. “Most programs,” Franta said, “have role portions to the course. We talk about seeking help early,” if the weight of the job is taking a toll. Also, said the veteran nurse and administrator, “If I see or think someone’s in trouble, I’ll talk with them. We intervene.”

And while schools are challenged to turn out qualified nurses, another challenge says nursesjournal.com is finding enough qualified instructors. Meanwhile, the healthcare deficit continues to grow even as salaries in the profession do, too.

Graduating nurses, said the CSU-Pueblo nursing director, can earn a starting salary of somewhere between $60- $80,000 per year. Salaries, of course, are predicated on location. Smaller communities will naturally have lower salaries. But in larger metropolitan areas, he said, nursing salaries can hover between $100-150,000.

Colorado now sits 21st in state ranking in nurses-to-patients ratio with an 8.95 per 1,000 patients ratio. Neighboring Utah has the country’s best nurses-patient ratio at 7.26 per 1,000 while Washington, D.C. ranks last with a 16.74 per thousand nurse-patient ratio.

Most of the nursing candidates at PCC and CSU-Pueblo are from Pueblo or the nearby region. But Franta thinks students considering the profession from Denver or other Front Range cities would be wise to consider Pueblo to train for a career he says has been fulfilling to him for more than 30 years.

“We’re a highly qualified program and do well at training nurses,” said Franta. “We believe and honor the mission of our university: “We’re the ‘People’s University of the Southwest.”

While Florence Nightingale may be the profession’s best-known nurse, it may be the words of another nurse who best sums up this invaluable vocation: “Nurses are a unique kind,” said nurse and professor Jean Watson. “They have this insatiable need to care for others, which is both their great- est strength and fatal flaw.”